.NET Blazor

Published

.NET Blazor has been touted as a revolutionary framework that allows .NET developers to build interactive web applications using C# instead of JavaScript. It's mainly aimed at ASP.NET Core developers who want to build SPA-like apps leveraging the .NET ecosystem and a wealth of existing libraries and tools available via NuGet. It's Microsoft's latest instalment in an attempt to gain traction amongst frontend developers. With the recent release of .NET 8 Microsoft announced even more improvements to Blazor, most notably introducing a new rendering mode called "Static Server-side Rendering (SSR)".

But what exactly is Blazor and how does it enable C# to work in the browser? More interestingly, how does it compare to traditional JavaScript based SPA frameworks with which it aims to compete with?

Blazor WASM

Blazor has been on a journey and in order to understand Blazor's current state one has to look at its evolution starting from the beginning. Launched in 2018, Blazor initially started as an experimental project, aiming to leverage WebAssembly to run C# directly in the browser, allowing developers to build SPAs using .NET. This idea was realized with Blazor WebAssembly, which allowed the .NET runtime to execute on the client.

Blazor WebAssembly, commonly abbreviated as Blazor WASM, offers the most SPA-like experience among all Blazor options. When a user first visits a Blazor WASM application, the browser downloads the .NET runtime along with the application's assemblies (lots of .dlls) and any other required content onto the user's browser. The downloaded runtime is a WebAssembly-based .NET runtime (essentially a .NET interpreter) which is executed inside the browser's WebAssembly engine. This runtime is responsible for executing the compiled C# code entirely in the browser.

Although Blazor WASM applications are primarily written in C#, they can still interoperate with JavaScript code. This allows the use of existing JavaScript libraries and access to browser APIs which are not directly exposed to WebAssembly.

While Blazor WASM has received plenty of initial praise and has been improved over time, it's also been met with key criticisms which often revolve around the following areas:

-

Initial load time:

The requirement to download the .NET runtime and application assemblies upon the first visit can result in a significant initial load time. This is even more evident in complex apps with large dependencies and especially over slow networks. -

Performance:

Blazor WASM lags behind traditional JavaScript frameworks in terms of performance. The WebAssembly runtime is still generally slower than optimised JavaScript code for compute-intensive workloads. -

Compatibility:

While WebAssembly is widely supported in modern browsers there may still be issues with older browsers or certain mobile devices which can limit the reach of a Blazor WASM application. -

SEO challenges:

Beside the usual SEO challenges which all SPA frameworks come with, the additional longer load times and slower performance of Blazor WASM can negatively impact SEO rankings. -

Complexities of interop with JavaScript:

While Blazor WASM allows for JavaScript interop, it can be cumbersome to use alongside complex JavaScript libraries or when there is a need for extensive interaction between C# and JavaScript functions. This complexity can lead to additional development overhead and potential performance bottlenecks. Unfortunately due several limitations the need for JavaScript interop is very common and therefore kind of undermines the whole premise of using Blazor in the first place.

Blazor Server

To counter act some of these critiques, Blazor Server was introduced a year after Blazor WebAssembly, enabling server-side C# code to handle UI updates over a SignalR connection. Unlike in Blazor WASM, the client-side UI is maintained by the server in a .NET Core application. After the initial request, a WebSocket connection is established between the client and the server using ASP.NET Core and SignalR.

When a user interacts with the UI, the event is sent over the SignalR connection to the server. The server processes the event and any UI updates are rendered on the server. The server then calculates the diff between the current and the new UI and sends it back to the client over the persistent SignalR connection. This process keeps the client and server UIs in sync. Since the UI logic runs on the server, the actual rendering logic as well as the .NET runtime doesn't need to be downloaded to the client, resulting in a much smaller download footprint, directly addressing one of the major criticisms of Blazor WASM.

However, while innovative in its approach, Blazor Server has several downsides of its own which need to be considered:

-

Latency:

Since every UI interaction is processed on the server and requires a round trip over the network, any latency can significantly affect the responsiveness of a Blazor Server app. This can be particularly problematic for users with poor network connections or those geographically distant from the server. -

Scalability issues:

Each client connection with a Blazor Server app maintains an active SignalR connection (mostly via WebSockets) to the server. This can lead to scalability issues, as the server must manage and maintain state for potentially thousands of connections simultaneously. -

Server resource usage:

Blazor Server apps are much more resource-intensive because the server maintains the state of the UI. This can lead to higher memory and CPU usage, especially as the number of connected clients increases. -

Reliance on SignalR:

The entire operation of a Blazor Server app depends on the reliability of the SignalR connection. If the connection is disrupted, the app can't function. This reliance requires a robust infrastructure and potentially increases the complexity of deployment, especially in corporate environments with strict security requirements that may restrict WebSocket usage. -

No offline support:

Unlike Blazor WebAssembly apps, Blazor Server requires a constant connection to the server. If the client's connection drops, the app stops working, and the current state can be lost. This makes Blazor Server unsuitable for environments where offline functionality is required. -

ASP.NET Core Server requirement:

The reliance on SignalR also means that Blazor Server apps cannot be served from a Content Delivery Network (CDN) like other JavaScript SPA frameworks. Serverless deployments aren't possible and Blazor Server requires the deployment of a fully fledged ASP.NET Core server.

Blazor Static SSR

Despite Blazor's versatility, both the WASM and Server rendering modes suffer from serious drawbacks which make Blazor a difficult choice over traditional SPA frameworks, which by comparison don't share any of Blazor's problems and are architecturally simpler too.

Being aware of these challenges, Microsoft tackled some of the primary concerns of Blazor WASM and Server by rolling out Blazor Static SSR:

Blazor Static SSR, as shown in the diagram above, is a third rendering option which operates entirely independent of WASM or SignalR, instead leveraging an open HTTP connection to stream UI updates to the client. This approach, known as static site rendering, involves generating web pages server-side and transmitting the fully composed HTML to the client, where it then gets wired back into the DOM to function as a dynamic application.

During an initial page load, Blazor Static SSR behaves similarly to a traditional server-side application by delivering a complete HTML page to the user's browser. Additionally, it fetches a blazor.server.js script that establishes a long lived HTTP connection to an ASP.NET Core server. This connection is used to stream UI updates to the client. This architecture is more straightforward, much like a classic server-rendered website, yet it provides a dynamic, SPA-like experience by selectively updating portions of the DOM and therefore eliminating the need for full page reloads.

The benefits over Blazor WASM and Blazor Server are twofold:

-

Reduced load times:

There's no need for users to download the full .NET runtime and application files when visiting the website, and as they navigate through the site, complete page reloads are avoided. -

Scalability:

No SignalR connection is required which greatly reduces the load on the server and removes many of the complexities around WebSocket connections.

Nonetheless, Blazor Static SSR is not an actual SPA framework in the traditional sense. It doesn't allow for rich interactivity beyond web forms and simple navigation. It also doesn't allow for real-time updates as there is no code running on the client after the initial page was loaded:

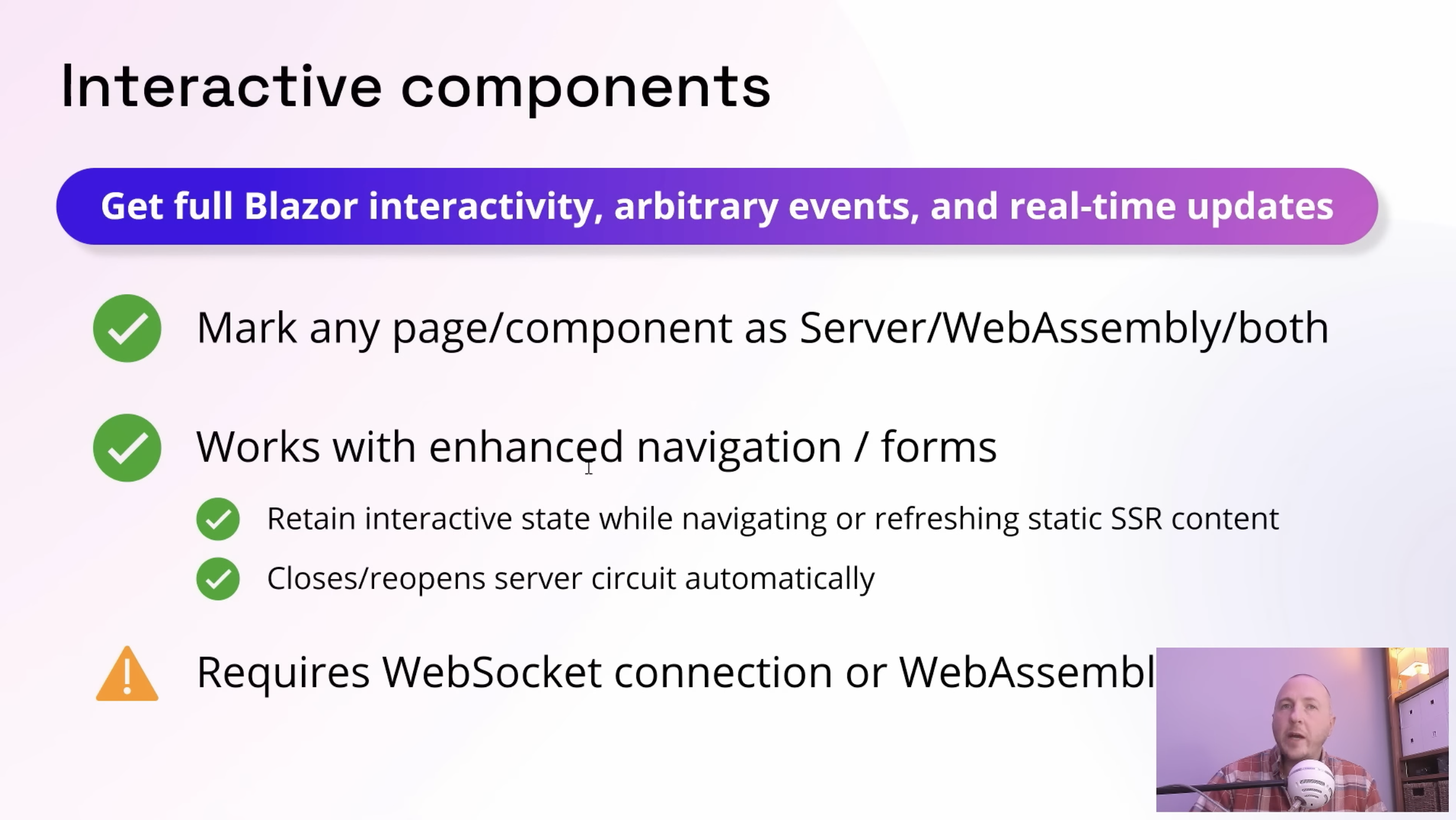

To combat this, Blazor starting with .NET 8 enables the mixing of different modes and introduces a fourth rendering option called Auto mode.

In order to add interactivity to a Blazor Static SSR website one has to go back to creating either Blazor WASM or Blazor Server components. The auto rendering option aims to counter the main issues of Blazor WASM's slow load times and Blazor Server's requirement for a SignalR connection by using both rendering modes at different times:

A Blazor component operating in Auto-mode starts off by establishing a SignalR connection to enable immediate interactivity and bypass extended load times. Concurrently, it discreetly fetches the .NET runtime and all necessary dependencies to function as a Blazor WASM application. For later visits, Blazor transitions from the Server to the WASM version, maintaining SPA responsiveness without further dependence on the SignalR connection.

It's a fascinating approach which undoubtedly doesn't lack creativity or ambition. Even so, Blazor Static SSR incorporated with interactive components poses some old and new challenges too:

-

No interactivity without WASM or SignalR:

The biggest drawback of Blazor Static SSR is that it still relies on Blazor WASM or SignalR to become an interactive framework, which means it inherits not just one, but all of the many unresolved downsides when running in Auto-mode. -

Increased complexity:

Combining three different rendering modes adds a lot of complexity on the server and presents a steep learning curve for developers who must comprehend and manage those complexities effectively. -

No serverless deployments:

Deployments from a CDN are still not possible due to the reliance on ASP.NET Core. -

No offline support:

Blazor Static SSR minimises full page reloads but still requires an active connection to stream updates to the UI. -

Caching challenges:

While static content is easily cacheable, dynamic content that changes frequently can be challenging to cache effectively, potentially missing out on valuable performance optimisations.

Having said that, Blazor Static SSR also comes with a few benefits when it's not mixed with WASM or Server together:

-

SEO Friendliness:

Since SSR applications pre-load all the content on the server and send it to the client as HTML, they are inherently SEO-friendly. This allows search engines to crawl and index the content more efficiently. -

Fast initial load:

Blazor Static SSR can provide faster initial page loads compared to SPAs. This is because the HTML is ready to be rendered by the browser as soon as it's received, without waiting for client-side JavaScript to render the content. -

Stability across browsers:

SSR applications often have more consistent behavior across different browsers since they don't rely on client-side rendering, which can sometimes be unpredictable due to browser-specific JavaScript quirks.

Blazor vs. traditional JavaScript SPAs

Overall Blazor is a remarkable achievement with buckets of originality and technical finesse, however with the exception of Blazor WASM, Blazor Server and Blazor Static SSR behave quite differently to traditional SPAs.

Neither Blazor Server or Blazor Static SSR load all the necessary HTML, JavaScript and CSS upfront. They have a hard dependency on an ASP.NET Core backend, can't be hosted serverless and require a constant connection to a server. The frontend is not separated from the backend and data is not fetched using APIs. Typical SPAs maintain state on the client side. The user's interactions with the application can change the state, and the UI updates accordingly without a server round-trip. Since SPAs don't require page reloads for content updates, they can offer a smoother and faster user experience that is similar to desktop applications. With conventional SPAs the same code can often be shared between web and mobile apps, another advantage over Blazor Server or Static SSR. The clean separation between the frontend and the backend makes the overall mental model simpler and allows to efficiently split the disciplines between different teams.

Blazor WASM vs. JavaScript SPAs

Blazor WASM stands out as the only rendering option which fully aligns with the ethos of a conventional SPA. Unfortunately the heavy nature of having to run the .NET Runtime over WebAssembly puts it at a significant disadvantage over comparable JavaScript frameworks.

Blazor Server vs. JavaScript SPAs

While Blazor Server is technically intriguing, offering a unique approach to web development, it paradoxically combines the limitations of both, a Single-Page Application and a server-intensive architecture, at the same time. To some extent Blazor Server represents a "worst of both worlds" scenario. Personally it's my least favourite option and I can't see any future in this design.

Blazor Static SSR vs. JavaScript SPAs

Blazor Static SSR deviates the most from the paradigm of a SPA. Apart from being placed under the Blazor brand it diverges significantly from the framework's initial architecture. Ironically this is where its strengths lie as well. Given that SPAs are inherently accompanied by their own set of challenges, the necessity for a SPA must be well-justified, or otherwise opting for a server-rendered application can be a more straightforward and preferable solution most of the times.

In my view, Blazor Static SSR is a compelling option that deserves to be its own framework, enabling .NET developers to enrich the functionality of everyday ASP.NET Core.

A word of caution

Would I opt for Blazor today? To be candid, probably not. While I maintain a hopeful stance on Blazor, I must remain truthful to myself. I've never been the person who blindly champions every Microsoft technology without critical thought. The truth is, currently Blazor is evolving into an unwieldy beast. In spite of its four rendering modes, intricate layers of complexity, and clever technical fixes, it still falls short when compared to established SPAs. This situation leads me to question the longevity of Microsoft's commitment and how long Blazor will be around. The parallels with Silverlight are hard to ignore, and without the .NET team delivering a technically sound framework, I find it hard to envision widespread adoption beyond a comparatively small group of dedicated C# enthusiasts who will accept any insanity over the thought of using JS.

An untapped opportunity?

As I reach the end of this blog post I want to finish on a positive note. I dare to say it, but could C# learn another thing from F#? Thanks to Fable, an F# to JavaScript transpiler, F# developers have been able to create rich interactive SPAs using F# for quite some time. Developed in 2016, Fable was originally built on top of Babel, an ECMAScript 2015+ to JavaScript compiler. Wouldn't something similar work for C#? As I see it this could pave the way for a very appealing C# framework that circumvents the complexities around WASM and SignalR.

Blazor not only in name but in glory too.

In fact, I'm quite surprised that we haven't seen such a development yet, but perhaps it's a matter of perspective. Maybe it has been a case of the wrong team looking at the wrong problem all along? After all the ASP.NET Core team excels in web development and not compiler design. Not every problem needs to be solved using SignalR or streaming APIs. Perhaps it's time to put a hold on more rendering modes and looking at Blazor through a different lens?

In my view, without doubt, this is the best path forward and I shall remain hopeful until then.